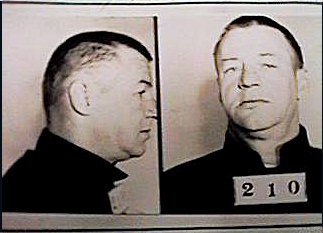

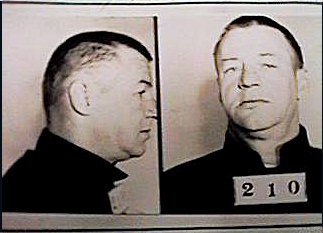

The Postal Inspectors knew they had the right man, but who was he?

Two men held up the Isaiah, California post office on October 2, 1931. They bound, gagged, and blindfolded the postmaster, his wife, and two patrons. Outside, a third man kept a lookout in his automobile while his accomplices stuffed what monies they could find into their pockets. The take was $16.53.

Sheriff C.W. Toland apprehended the lookout in Oroville, California on October 22. John L. French quickly identified his accomplices as Joe Miller and James H. Clampitt. Frank J. Kerrigan, United States District Judge in Sacramento, allowed French to plead guilty in exchange for his testimony and three years probation. French blamed Miller for pressing him into the crime. On March 9, 1932, Seattle police arrested Joe Bowers who matched Miller's description. Postal Inspector Bernard Mein travelled to Seattle and interviewed Bowers on March 15, at which time Bowers confessed to being Joe Miller. He was returned to Sacramento, stood trial, pled not guilty, and received a sentence of twenty-five years for Violation of Postal Laws (robbery).(1) Clampitt remained at large. Shortly thereafter, Judge Kerrigan met with the United States Attorney, Albert Sheets, and decided to recommend Bowers for parole when he became eligible. Kerrigan wrote to Bowers to tell him of his resolve.(2)

The news cheered Bowers. Kerrigan wrote to him at McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary, Washington, to give him heart and to clarify Bower's situation:

I was glad to learn that my saying that I would recommend parole for you has given you new hope and courage to change your manner of living. I want you to fully understand that whether or not you receive a parole depends entirely upon you and your behavior in prison up to the time you become eligible for parole. If your conduct is not good and if you have not cooperated with the prison authorities in every way, my recommendation that you be paroled will have absolutely no weight with the Parole Board. You must earn your parole yourself.(3)

The man who postal inspectors had first pursued as Joe Miller proved to be a confounding case for the Bureau of Prisons. The Bureau of Investigation had traced an arrest record that had begun in 1928 when Bowers was arrested in Portland, Oregon for the theft of a automobile and sentenced to ten months in the Multnomah County Jail for violating the Dyer Act. Bowers told the McNeil Island social worker that he'd been a tunnel foreman on the Aerial Dam, near Woodland, Washington. An accident, he said, had ended that term of service. Federal officials contacted Portland's Inland Power and Light Company from whom they learned they learned that Bowers had been employed as a Miner and a Shifter until he quit without explanation in January, 1930. He was next arrested in November, 1930, for drunken driving, sentenced to 30 days in the Vancouver, Washington City Jail, fined $75, and released with his license suspended for ninety days. Bowers had trouble remembering his other jobs and even what he did before 1928, though he knew he'd been to sea and had worked as an interpreter in Germany.(4)

Bowers told McNeil Island officials that he'd been born in El Paso, Texas on February 18, 1897. His parents were circus people. He claimed that they'd deserted him as a baby when he was a mere two months of age. They left him with friends, he said, who raised him in the circus until he was thirteen, when he left the life of the rolling wheels for that of the rolling sea. Though he'd never had any formal schooling, he could read and write six languages.

His biggest frustration, he said, was that he could not establish his citizenship. He wanted to work in France or Italy as an interpreter and needed to get a passport. He hated living in the United States because he needed so many papers and references to get a steady job. Bowers told Dr. Romney Ritchey that he'd worked as a seaman until the First World War broke out. After the war, he married a Russian woman in 1919, but this union did not last and he had no children. In 1922, he got a job as an interpreter, but lost this because he was not a German citizen. Following this disappointment, Bowers said he returned to the United States to prove his American origins. He wasn't successful, so he held many short term jobs until 1928 when he was arrested with another man who happened to be driving a stolen car. Ritchey observed that Bowers could explain away every offense he'd been charged with. Of the post office robbery, Ritchey reported that Bowers said:

...he was out of funds and actually hungry most of the time. Says he met a man sleeping in a Park in Sacramento who persuaded him to go along while they robbed a store and post office near Orville California. He claims that he did not actually go with the man to Orville but that the man himself proceeded with his plan and robbed the store and finally was arrested and confessed and layed the blame on Bowers, he himself going free for his testimony.(5)

This latest incarceration seemed to Bowers to be yet another knot in an interminable rope strung for him by officers of the law who did not like him because he could not prove his birthplace. Things would be all right, he told Ritchey, if he just had the chance to establish who he was. Then he could get work either in the United States or one of the many foreign countries where he'd worked as an interpreter.

A physical showed that Bowers was in excellent health. His right testicle was missing due to a gunshot injury during the Great War and there was a second bullet wound on his back. When telling Ritchey of his woes, Bowers grew passionate:

He denies having any hallucinatory experiences of any kinds but admits he worries a great deal about his condition and especially about his sentence. He asserts that he is an honest man and tries to do right at all times and does not understand why he cannot get along better. He is quite unstable in his emotional field and says he has never had any very close friends. He has wandered from place to place all his life never remaining more than a short time at one location. Something always happens to his job which makes it impossible for him to remain. This never results from any fault of his own he thinks, but from circumstances over which he has no control.

Ritchey concluded that Bowers sufferered from a "constitutinal psychopathic state. Inadequate personality. Emotionally unstable. Without psychosis."(6)

McNeil Island authorities despaired in their dealings with Bowers. He begged them for help establishing his citizenship. They responded by transferring him to Leavenworth. Here, in June, 1933, he suddenly claimed amnesia and wrote to the German Seaman's Department asking for their help in discovering who he was. "I do all my thinking in German", he told them. "I must have been born somewhere in Europe or else I've been on quite a few German boats."(7) Abandoning his circus origin myth, he evinced his desparation to discover who he was.

The letter concluded with a plea to send "any kind of paper...or any kind of record" to authorties at Leavenworth so he could know who he was.(8)

German Veterans officials responded to Leavenworth's warden in August. Josef Ebner, as they called Bowers, was not a German subject nor had he taken part in the war. He appeared to have been born in Rohrbach, Austria on February 18, 1897. He'd served on German ships as a stoker or fireman for about six months in 1921 and 1922, but had deserted his last post at Las Palmas, Spain. Due to the redrawing of European boundaries, Ebner was now subject of Czechoslovakia. All further inquiries were directed to the Czech ambassador in Washington.(9)

The following year, Bowers asked to be deported. He shortly thereafter learned that because he'd only been sentenced once to a term of one year or more in a crime involving moral turpitude, that under U.S. Law, he could not be deported. It may have seemed, at first, that the nervousness he exhibited was only a product of this disappointing news. But Bowers also had difficulty breathing and he was aware of a tightness and thickening of his neck. Leavenworth's Dr. Williams examined him late in May and ordered an emergency operation: Bowers suffered from a "bilateral hypertrophy thyroid". He was removed from his cell and brought to the hospital where the malfunctioning gland was excised.

Two months later, he fell on his head while standing, talking to another prisoner. He fainted, cutting his scalp on the steel framework of a cellhouse door. Chief Medical Officer K.R. Nelson stitched the wound shut and gave Bowers a tetanus shot.(10)

Joe Bowers was, by all reports, a sick man. While at Leavenworth, he'd been troublesome only twice, once when he'd checked himself into the prison hospital and then wanted to leave again; and a second time when he was caught with a contraband deck of Bicycle playing cards.(11) Aside from this and from his nervous disposition which was clearly due to his glandular problems, there were no reports which suggested that he was a custodial problem or guilty of any particularly heinous violations of the moral order. His health problems marked him as a candidate for the Federal Medical Penitentiary in Springfield, Missouri, where doctors could deal with the depression and other symptoms of hypothyroidism that were sure to follow his May operation. Instead, on August 18, 1934, Warden F.G. Zerbst received an order from Washington to send Joe Bowers to Alcatraz.(12) His partner, Joe Clampitt, was sent to Springfield, from which he escaped in a few months.

No one seemed willing to take responsibility for or take action to fix an obvious mistake.