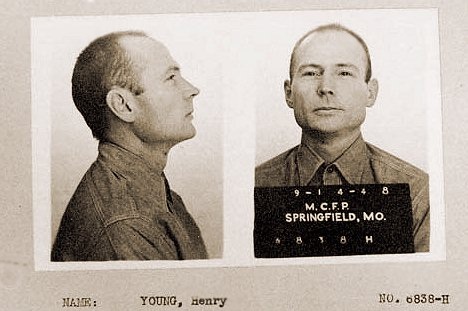

![]()

Henri Young had had only three years of freedom before he stole money from the Miles City "degenerate". His freedom between sentences was brief. He'd become a man in prison and learned some better ways to grab a dollar for himself out of the purse of another. When he sat before his classification committee at McNeil Island, he boasted of his role in the crime spree that had culminated in the abortive robbery of the Lind, Washington National Bank. He seemed calm to the social worker, proud of his vagabond life and decidedly unconcerned about the future. The psychiatrist thought him bright and unstable. The Deputy Warden, the social worker, and the psychiatrist all called Henri a "dangerous criminal". Henri, himself, appeared to have decided to be such.

The Classification Committee recommended close custody and constant psychiatric oversight. Though the Deputy Warden spoke against it, the Committee advised the Bureau of Prisons that he should be transferred to Leavenworth "in order to break up dangerous partnership with co-defendant #11247-M", namely Sherman Baxter.(1) Washington has a new prison to fill. The Bureau had him packed in a "shipment of furniture" (which included the Weyerhauser boy's kidnapper Harmon Waley) which was delivered to Alcatraz on June 1, 1935.

On June 30, Young got in trouble for the heinous crime of "loud laughing and talking in the mess". Guards had known for some time that someone was violating the sacrosanct Rule of Silence, but until Mr. Haboush turned unexpectedly, they did not know who was doing it. Henri and his accomplice, mail robber Francis Keating (130-AZ) were warned not to do it again. Eighteen days later, he refused to shake out some clothes. "I did my job," he told the foreman, "and I am not going to do any more." The laundry room guard, Joe Steere, walked up and asked Henri if he was refusing to do it. "Yes sir, I do," Henri replied crisply. For this, Deputy Warden C.J. Shuttleworth sent him to solitary where he received bread and water except for one good meal every third day. Shuttleworth released Henri on the 30th and restored all his privileges on August 9th.(2)

Less than a month after this, Henri imagined that he saw worms in his soup. Mr. Dixon carefully inspected the broth and declared it eatable. Shuttleworth fined Young his supper. For smoking after the first whistle had blown, Henri received a warning.

The door of solitary opened again for Young after Mr. Faulk, acting on a tip, searched a laundry truck in the elevator and found $25 in contraband currency destined for the pocket of mail robber Harold Montgomery (67-AZ). Young admitted sending the money after Montgomery had asked for it via the prison grapevine. He denied handling any more money and said he didn't know where Montgomery got it. Young's conduct report shows that Shuttleworth believed the last claim. When Shuttleworth freed Henri, he put the convict to work in the kitchen.(3)

The Alcatraz regimen which dictated such crimes and punishments bred wrath among the convicts. Prisoners resented the silence system, delays in receiving their mail, and the lack of "good-time" compensation for the hours in the Rock industries. On the morning of January 20, 1936, some of the men in the laundry left their work stations and called to the others to join them. They gathered on the first floor where they waited until Deputy Warden Shuttleworth got word of the revolt and sent down reinforcements. The guards lined up the strikers, warned them, and, then on Warden Johnston's orders, marched them to the cell house and locked them in their cells.

The following morning twenty four kitchen workers, including Henri Young, joined the laundry wildcats. Young showed his solidarity by dumping four hundred pounds of vegetables in the kitchen basement before leaving his post. He was intercepted on the way to his cell and placed in the D-Block "open solitary". Seven of his brother convicts received a worse treatment: Johnston had them placed in the relic Army-era dungeon beneath the cell house.

The revolt of the kitchen workers left the chief steward without manpower to keep the nonstrikers fed. A call went out for volunteers to help in the kitchen, but none of the nonstriking workers would scab. As Henry Larry explained "We told the guards we would continue to do whatever work we had been doing, but nothing more." Prison authorities did not force the issue with the nonstrikers. Eight guards were delegated to the task of preparing and serving the food:

That may not seem very humorous to free men, but to us on Alcatraz it was better than a Charlie Chaplin comedy. The fact that they couldn't enforce the silence system while the strikers were making so much noise made it funnier yet. The guards, with aprons tied around their middles, had to carry the food in and take a lot of kidding while they did it. Some of them took it all right and kidded back, but others looked like they were going to have a stroke.(4)

Three strikers went back to their jobs the following day. The guards brought the rest water, but no bread until the morning of the 23rd. Henri Young joined in the heckling of the guards and convicts who returned to work. "Here they come with some more of that sauerkraut", he was reported to have shouted as Officer Morrison ascended the stairs. Young did his part to enjoin his fellows to stay on strike, but by Friday afternoon, the 24th, he, too, was begging to be allowed to return. Shuttleworth released him from solitary the next day, stripping Young of all his privileges "and with the understanding that further discipl. action might be taken later". Though Young played a leadership role in fomenting the kitchen strike, he did not hold out nearly as long as some of his compatriots. Fifteen prisoners declared a hunger strike on February 15. On the 18th, the chief physician began force-feeding these men. Five gave up promptly. Ten others took the tube. The alimentary rape continued through the end of February as two of the men still refused to eat. But the strike was over and Johnston claimed victory.(5)

Young did not stay out of trouble in the interval between the 1936 strike and the one that began in September, 1937. Guards reprimanded or punished him for things like wasting food, refusing to pass his empty cup to the end of the table, talking in line with fellow inmate Joseph Urbaytis (213-AZ), screaming at the top of his lungs in the cell house, and stealing a pair of Army issue socks from the laundry. On September 20, 1937, Young and several other prisoners remained in their cells after the noon meal. "I just can't take it and I am not going to work," he told the new Deputy Warden, E.J. Miller. Miller reported Young as one of the leaders of the strike and had him locked up in solitary.

After his return to the isolation population of D-Block, Young continued to antagonize officers by yelling at the top of his lungs, talking to other prisoners, making obnoxious sounds with his mouth, and tapping on the bars with his cup. Once he demanded seconds of food. When guards denied him his request, he threw his tray out the cell door. Miller threw him into solitary in early October, 1938 after Young came out of the Hole following the tray incident and again started screaming at the top of his lungs. On October 17, 1938 -- a date which Young committed to memory -- he emerged from Alcatraz's sensory deprivation chamber and, to all appearances, became a model prisoner.

Somehow, Young had made the acquaintance of another Missouri-born bank robber and kidnapper, Arthur "Doc" Barker, one time leader of the Barker gang.  Barker had formed a new gang in prison, consisting of some old friends (including Alvin Karpis) and some new ones such as his coworkers in the mat shop, Rufus McCain and William Martin. For two years, Barker had tested the Rock's security, mentoring the attempts, first by Cole and Roe, and then by Limmerick, Franklin, and Lucas, to break out of the Model Industries Building during daylight hours. Limmerick had been killed by Mr. Stites. Franklin and Lucas were confined to isolation. But Cole and Roe had simply disappeared. Many convicts believed that they'd made it all the way to South America. Though Doc knew that they'd drowned in the undertow off the northwest point of the island (Alvin Karpis had seen it happen), he believed that escape was possible. This time, he planned to make the break at a point where Warden Johnston and the guards thought themselves the strongest: the tool-proof window guards of the D-Block isolation unit.

Barker had formed a new gang in prison, consisting of some old friends (including Alvin Karpis) and some new ones such as his coworkers in the mat shop, Rufus McCain and William Martin. For two years, Barker had tested the Rock's security, mentoring the attempts, first by Cole and Roe, and then by Limmerick, Franklin, and Lucas, to break out of the Model Industries Building during daylight hours. Limmerick had been killed by Mr. Stites. Franklin and Lucas were confined to isolation. But Cole and Roe had simply disappeared. Many convicts believed that they'd made it all the way to South America. Though Doc knew that they'd drowned in the undertow off the northwest point of the island (Alvin Karpis had seen it happen), he believed that escape was possible. This time, he planned to make the break at a point where Warden Johnston and the guards thought themselves the strongest: the tool-proof window guards of the D-Block isolation unit.

Young's antics at the expense of the guards must have impressed Doc: The same day that Young got back to his isolation cell, someone handed him three eleven-inch hacksaw blades which had been sneaked past the electronic snitch boxes and passed over to D-Block from the Main Cell House. Until Doc arrived in isolation in November, played the leading role in the escape preparations. He set to work on the bars hiding the blades in the underside of his cell shelf and using aluminum paint and some putty to cover the saw marks.In five days, he cut through. Rufus McCain (267-AZ) began cutting the bars on his cell two weeks after Young broke through. William Martin (370-AZ), a black mail robber from Chicago, began to cut at the same time as McCain. They would be joined by Barker (268-AZ) and Dale Stamphill at the end of November. In the meantime, Young started on the window guards alone.

The cell house bars were easy to cut. They'd been installed in 1910-11 when the Army first built the Cell House. Johnston had stripped out most of the soft strap-steel which caged prisoners while Alcatraz served as a disciplinary barracks and replaced it with tool-proof steel in 1933-34. B and C Blocks were completely converted, but for reasons of economy, A and D blocks were not done. Both these units were used as "maximum security", a designation which prisoners in the know about the pliability of the barriers found laughable.

The tool-proof bars on the windows posed a different challenge. A steel matrix surrounded a tool resisting carbon or alloy steel core. The two components were welded throughout the length of the bars. "Our saws went easily through the outer layer," Young told The Examiner's Alvin D. Hyman two and a half years later, "But when they hit the core, it was just like drawing a finger nail across a piece of glass."(6) Official BOP specifications defined a "tool-resisting bar or plate...as one which is not severed within a working period of six hours by using six hand hacksaw blades or pierced by using six 1/8" bits used in hand-operated or motor-driven drill".(7) Though the designers did not believe that their creation was unpenetrable, they felt confident that it would resist the most ordinary attempts to escape.(8)

The break which finally happened on January 13, 1939 proved an exceptional one. The Barker gang contrived a pressure jack, with a five-eighth's inch screw mounted inside which could be turned with a wrench. Young, McCain, and Martin had observed the comings and goings of the guards for some time and had concluded to conduct their work during meal times, when the noise of the Cell House and the required counts and line up of the general population distracted the guards from observing their D-Block charges. Using the pressure jack, they bent the tool-proof bars back and forth. Three times caused the bars to snap like wire. While McCain and Martin worked the jack, Young climbed up on the roof of D-Block and kept watch on the gun-cage guard. The first time he did this, he "realized that [he] had taken a wild chance in working on those windows without a lookout; [he] might have been spotted by the gun guard and shot to death."(9)

A heavy fog on a dark night gave the quintet its chance to run. They grabbed the sheets off their beds, spread open the bars of their cells, crossed the empty corridor at about 3 a.m., opened the prepared window guard, and slipped out onto a roadway, in full view of a guard tower. The mist obscured their movements, however, and they made their way to a beach along the southwest tip of the island, picking up bits of scrap lumber along the way. Young remembered:

My heart was in my mouth. I felt strange, nervous, like a man in a dream. On the beach we hurriedly threw together a makeshift raft, tying the lumber we had gathered, with the sheets we carried. We stripped and made bundles of our clothes and put them on the raft. We swam out, pushing the raft before us. Thirty yards out, McCain called a halt. He said that the raft was weak, in danger of falling apart. He insisted on going back for more lumber to strengthen our raft.(10)

Young and his companions paddled back to shore. They gathered more wood and set out once more. One hundred yards out on the calm water, McCain panicked again. He begged his companions to go back and get more lumber. They did. The noise of the waves and the clambor of their feet across the rocky beach covered the sound of the siren ringing above. A guard boat appeared out of the fog and shots were fired. While Barker and Stamphill beat it into the fog, McCain and Young stood still, holding up their hands. Guards hurried the naked men past Warden Johnston and up to the hospital. Dr. Romney Ritchey, the chief physician, personally examined them. As they waited in the hospital, guards brought Doc and Dale Stamphill on stretchers. Associate Warden Miller escorted a bruised William Martin in a little later. Doc would die later that day of a skull fracture which spread from a point behind his right eye. Doc's dream of embarassing Warden Johnston with a successful breakout from the most secure section of the prison died with him.

Henri never tried again. Instead, he continued his feud with the guards and started a new one. His enemy was his former partner in flight, Rufus McCain.

![]()

![]()