![]()

The Rock was intended for men the Justice Department wanted forgotten. But from the day when the first "shipment of furniture" arrived on the island, Warden Johnston found that he could not keep mainland eyes from scrying Alcatraz's silhouette. As men were freed from the prison and released from Johnston's Rule of Silence, they talked. They talked about the regulations. They talked about the dungeons. They talked about Al Capone, Alvin Karpis, Arthur "Doc" Barker, and "Machine-Gun" Kelly. Reporters waited at the docks as freed prisoners alighted from the General McDowell and vied to get the exclusive rights to a tale of the unseen world inside the Cell House walls. The public enemies did not lose their faces or their names. Unknown men, troublemakers known only to the staff, came to tell their stories and the stories of others to a public eager for details about what some called "America's Devils Island".

Johnston had been stung a few times by these accounts. A letter from an unknown convict was smuggled off the Rock and appeared in the city newspapers naming three men, John Standig, James Groves, and Joe Bowers, as the cringing products of Alcatraz's sensory deprivation chambers. Henry Larry told the world about the dungeons and the shooting of Joe Bowers. A.W. Davis and Pet Reed wrote series which ran in the local papers. Bryan Conway's memoir of his 20 months on the Rock appeared in the august Saturday Evening Post.

No matter what Johnston and his staff did, they could not keep these tales off the news stands. He'd designed the Rule of Silence as a hedge against information which could be used by outsiders to plan an escape: the press reported it as a torture. Men who were cautioned not to speak about the Rock checked their parole status and spoke if their freedom could not be summarilly revoked by a court or oversight board. The Bureau of Prisons did not always cooperate with Johnston's plans to keep Alcatraz secure: for example, it often forced him to release convicts directly from the Rock, with the news of its tragedies and routines fresh in their minds. Sometimes they embellished their accounts a little: tales of underwater dungeons designed by Spanish torturers and an extensive tunnel system romanticized many a picture of life on The Rock.

Organs run by political opponents of the Roosevelt Administration were quick to reprint the stories and comment upon the character of those who ran the Rock. H.L. Mencken's The American Mercury printed the most infamous of these polemics, Anthony Turano's "America's Torture Chamber", in September, 1938. Amid articles which likened New Deal reforms to Soviet five year plans, which called those who voted for the Democrats fools, or which told Jews to convert to Christianity so that there would be no more "Jewish problem", Turano painted a dark picture of Alcatraz where Warden Johnston loomed as "the duly-consecrated Torquemada of the place"; where Rufus Persful chopped off part of his hand; where guards "entertained their charges with a peculiar lullaby consisting of the staccato of target practice conducted near the cell house"; and where Al Capone spent "his time singing operatic arias, in utter oblivion of the silence rule, while he childishly makes and unmakes his prison cot."(1)

Many of Turano's tales were true , but he neglected to mention that reforms were being made. Under pressure from Washington, Johnston eased up on the rule of silence, ended the target practice, and put a stop to the use of the dungeons. When San Francisco citizens panicked after the death of "Doc" Barker (not because Barker had been killed but because he'd gotten out of the Cell House and might have made it to shore) the warden persuaded the Bureau of Prisons to completely rebuild "D"-Block. By late 1940, he'd addressed many of the concerns that had appeared in the papers.

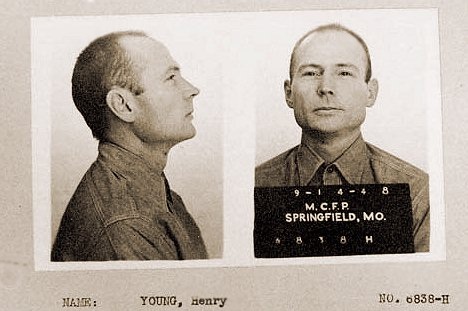

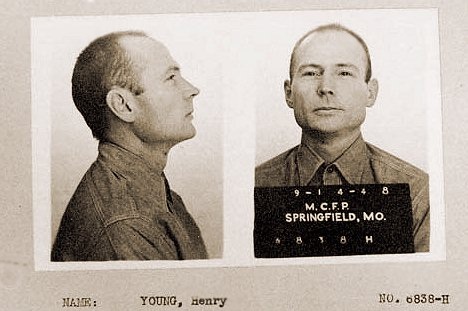

As Henri Young was removed from the Rock on February 12, 1941, and taken to the mainland to be arraigned, Johnston must have felt at ease. The prosecution had what seemed to be a clear case of murder in the first degree against a penniless man with no lawyer. Young grimaced and protested as news photographers took a picture of the handcuffs being removed from his wrists before he entered the court room. His eyes, The Examiner reported, widened as he beheld the mahoghany grandeur of the trial chamber. U.S. Judge Michael J. Roche entered the room and Young snapped to attention. He listened to the reading of the indictment in complete silence. As the court clerk finished and handed him the paper, Henri thanked him and turned his attention to the judge.

Roche asked Young if he had an attorney. Young indicated that he did not. He was asked if he could afford to retain one. Young answered in the negative and then made a request which made the front pages:

Categorically speaking, I have a preference in lawyers. The more youthful my lawyers are, the better. I should like to have the court appoint two youthful attornies of no established repution for verdicts or hung juries. I want no attorney who has a reputation in San Francisco for receiving verdicts. I should like the most youthful attornies I can get.(2)

The request surprised Judge Roche, but he granted it. Roche appointed Sol Abrams and James M. MacInnis to represent Young. Abrams and MacInnis paid a visit to the Rock on the 18th. They asked to see the files of Young and McCain. This was denied, pursuant to BOP Order 3229 dated May 2, 1939. They also asked to see and photograph the Tailor Shop, where the stabbing had occurred and arranged to have Young brought to the U.S. Marshall's Office in San Francisco where they could interview him at length.(3) On February 21, 1941, Young was returned to San Francisco to meet with MacInnis and enter his plea: Not guilty.

The court set April 15 as the day for the start of the trial and on that day, the members of the jury were selected. This task done, the dueling attornies gave their versions of the stabbing. U.S. Attorney Frank Hennessy described how Young left his place in the Model Shop, went down the stairs to the Tailor Shop and drove his handmade knife into McCain's gut. As he was led away, Hennessy told the jurors, Young remarked "I think I killed the ---" a statement he subsequently amended to "I HOPE I killed the---".

Abrams rebutted nearly everything Hennessy had to say. Young, he insisted, had no inkling of what he had done until he found himself sitting with Deputy Warden E.J. Miller, listening to questions about the slaying. Abrams' defense of Young was one of irresistable impulse. Henri Young, he was to prove by the testimony of his witnesses, did not and could not perceive what was happening around him or what he was doing. It could not be argued, therefore, that he intended to kill Rufus McCain. It could not be said that he had committed the conscious, premeditated act of murder.

McCain, Abrams said, had made homosexual advances to Young and, for this, Young had struck him. Then, said Abrams, McCain moved in on the escape plot which Young and Barker had hatched together and, after McCain's pleas had forced the group to return twice to shore, it was McCain who first threw himself to the mercy of the guards. Young, who refused to sell out after the capture, found himself in perpetual isolation, and in this environment of sensory deprivation, brooded and brooded until McCain became, in his mind, "not a human being, but...the embodiment of evil".(4)

Johnston often claimed in interviews and before the court that nothing happened on Alcatraz that he didn't know. Abrams, however, surprised him with a question about the tipple made of milk and gasoline which went hand to hand between the cells and which Young had sometimes imbibed. Johnston confessed that he did not know this drink.(5) Chief Surgeon Romney Richey, when asked if he'd noticed whether Young had been nervous, replied "That's more or less his natural state."

"We are putting Alcatraz on trial," Abrams would announce to the court the following week.

...but we can't help that. We must show it in its true light. We're trying to show the effect of those conditions on Young's state of mind, his mental condition. We'll show a legal defense -- that Henri Young had no intent --therefore must be acquitted.(6)

The jury did not hear much of the evidence which Abrams and MacInnis hoped to introduce. But the questions were asked and some glimpses of life on the Rock, as well as accusations of staff brutality, found their way into the record and into the newspapers. A standing room only crowd came the day the Weyerhauser kidnapper, Harmon Waley (248-AZ), sat in the witness box and told about being thrust into solitary after asking for relief from a cold:

The doctor said he would send some [medicine] down to my cell at night. I told him I was sick, to take my temperature and see, but he wouldn't do it. Then I asked for a couple of aspirin at least, but he said he would send some to my cell at night. So I made a remark to him...they put me in the dungeon for three days because I was raving with sickness. I was beaten up. I was half crazy. I was put in a strait jacket.(7)

The defense put the word of the kidnappers, robbers, murderers, and other denizens of America's demimonde against that of the staff. After Abrams elicited testimony charging that Deputy Warden E.J. Miller had beaten or otherwise cruelly treated Young and other prisoners, he brought Miller back as a hostile witness. Abrams asked Miller if he'd ever hit a prisoner, seen a prisoner hit, or ordered one to be hit. Miller denied every allegation. Earlier, as he cross-examined one of the convicts, Abrams stopped in the middle of an "offer of proof" of the charges and told the court"I don't believe we have obtained the truth from Associate Warden Miller in 2 per cent of our questions. I would rather believe any of these convicts than believe Miller."(8)

It was all too easy, Abrams implied to the jury, for these men in power to fudge the record, to rely on the faith of their guards, and to present a false story to the jury. The prisoners, on the other hand, were helpless victims, who could not easily tell their story to the world because of the prejudice against their past wrongs and the strict controls over their mail and other communications with the outside. The ones who testified, said Abrams, risked their peace of mind at Alcatraz. They'd been threatened, frightened by the guards who'd tried to prevent them from testifying. Abrams wanted the jury to forget the inmates' criminal records and remember the horror -- the horror of the dripping darkness beyond the sight of ordinary men, where men lost their minds and grew murderous amid foulness, men named Joe Bowers, James Groves, and Joe Vigorous. The living among them were brought to testify. The defense named five men who had gone five to ten days without a meal. From Miller himself, Abrams brought the concession that Young had been out of isolation only 25 to 30 hours in three years and two months.(9)

Though Hennessy objected to this line of questioning and Judge Roche sustained him, Abrams persisted in bringing these issues to the attention of the jury. Following the parade of alledged Alcatraz victims, Abrams brought Henri Young to the stand. Young told the story of the stolen flashlight which cost him 15 unwarranted months at Deer Lodge, Montana and which pricked him into undertaking a more serious criminal career. He told the court that he'd first been sent to solitary for refusing to work in the prison laundry, work, he said, that was beyond his energies.

He described the dimensions of the solitary cell (nine by five by seven feet). On his introduction to the sensory deprivation chamber:

My clothes were taken off and I was placed there nude....After my clothes were searched for particles of tobacco, they were thrown into me. But not my shoes. I had no tobacco, no soap, no toothbrushes. It was like stepping into a sewer because of the bad plumbing.

His warders threw in two blankets at about five P.M. He had no bed or other furniture. Every morning they brought him a few slices of bread. Every five days, they gave him a full meal. He spent thirteen days on this occasion.(10) And there would be others. Once he'd observed the guards giving another man a "bath": they threw a bucket of cold water on him.

"The cell," he told the jurors,

is called 'The Icebox' by inmates. There is an old-type ventilator in the wall, open to the winds of the Golden Gate. I shivered all the time. I was in my stocking feet on concrete. At times I would get in a corner and put my coveralls around my head to keep warm. Then I would move them down around me. When you walk in the black cell you have to keep one hand on a wall so you won't get dizzy or hurt yourself.(11)

While Henri sat in isolation, he often dreamed dreadful dreams of McCain and the sexual advances he'd made to him. He became so distraught, Young said, that he put his mattress against the wall and beat his head against it. This, one might surmise from the testimony, became more or less his natural state in the maximum security unit after the escape attempt.

When Abrams brought him to speak of the slaying, Young said that he'd blacked out after McCain had insulted him. His first subsequent memory was of Associate Warden Miller asking him why he'd killed McCain. The question of the origin of the knives remained to be asked and when it was put to him, Young said that he'd found them both under a lathe. "Knives are common on Alcatraz," he said simply.(12)

As the trial wound down and the jury went into deliberation, the press sought out Young and his lawyers for more stories. James MacGinnis made headlines when he claimed that he had single-handedly talked an unnamed group of convicts out of attempting an escape from the packed courtroom.(13) Henri Young told his story of how they'd pulled off the escape back in 1939. Here he presented a slightly different picture of McCain which, if the jury had heard it, might have led it to a different conclusion: that Young had killed McCain out of anger for botching their escape attempt.

Media coverage had BOP officials concerned. Throughout the trial, journalists gave most of their attention to the claims of the defense that Alcatraz operated as a place to provoke despair in its charges. Only occasionally did they remind the public of the infamy of the convicts who testified. Director Bennett sent Warden Johnston the following telegram:

WHEN VERDICT IN YOUNG CASE HAS BEEN ANNOUNCED THINK YOU SHOULD GIVE OUT STATEMENT PROTESTING TACTICS USED BY DEFENSE IN EFFORT MAKE ROMAN HOLIDAY OUT OF TRAIL AND EVIDENT EFFORT USE TESTIMONY KNOWN TO BE ENTIRELY INADMISSABLE STOP DENY IMPLICATIONS OF QUESTIONS AND DENY THAT ANY CORPORAL PUNISHMENT OR CRUELTY EVER UTILIZED STOP ALSO SHOW THAT INMATES CALLED WERE MOST UNRELIABLE AND ANXIOUS EMBARRASS INSTITUTION SINCE THEY HAVE NOTHING TO LOSE STOP THINK SOME SUCH STATEMENT SHOULD BE GIVEN OUT REGARDLESS OF VERDICT STOP WILL BE GLAD TO GIVE OUT HERE IF YOU THINK WISE.(14)

The jury produced not only a disappointing verdict, but also an amendment which set Johnston and Bennett scrambling to respond. Foreman Paul Verdier, president of the City of Paris Department Store, stood up and announced their decision: Young was guilty only of manslaughter, a crime for which the maximum penalty was three years. Verdier then read a telegram, drafted by the jury of six men and six women, which he sent to the state's Congressional delegation, J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI, and BOP Director James Bennett:

It is my duty to inform you on behalf of the jurors....that it is our added finding that conditions as concern treatment of prisoners at Alcatraz are unbelievably brutal and inhuman, and it is our respectful hope and our earnest petition that a proper and speedy investigation of Alcatraz be made so that justice and humanity may be served.

"There is no inhumanity or brutality...at Alcatraz," Johnston fumed. The faith of the jury, Johnston suggested, had been snared by an old and shifty defense tactic, that of avoiding trying the person who has been charged and putting his victim and his prosecutors on trial. (15) James Bennett released a statement the following day which plainly stated that he had the greatest faith in Warden Johnston. The statement quoted the U.S. District Attorney as calling Young "the worst and most dangerous criminal with whom they had ever dealt"; and registered Judge Stanley Webster's solicited opinion that Young was "one who would not hesitate to kill anybody who crossed his path." There would be no investigation of Alcatraz because, Bennett said, there was no need.(16)

The press, which had reported each of the charges against Johnston and Alcatraz with relish, now rushed to exculpate itself from sensationalizing the trial by condemning Henri Young for "what he was". A May 4 article in The Examiner described Young's entrance into the courtroom on the day of his sentencing "with his lips wreathed in the same confident smirk that has characterized him throughout the murder trial." Young started to thank Judge Roche for honoring his request for inexperienced attornies. Roche angrilly interrupted him:

As long as you've opened this proceeding to comment....I will say that I've known Warden Johnston for thirty years and watched his work as a penologist with pride. His work is known and famed in this community and elsewhere. He's a man of outstanding ability and intelligence. So far as I know, the only mistake he ever made was in removing you from isolation, letting you go to the prison workshop, where you had the chance to...plan a cold-blooded, deliberate murder. You took a man's life without provocation. I've sentenced men to the gallows for far less.(17)

The press was through with its coverage of Henri Young's "vacation from Alcatraz". Young returned to the place of forgotten men. The next time a San Francisco newspaper ran a series about Alcatraz, defense pictures from Young's trial would be used to show how humanely the prisoners were treated.(18) A few months later, the eruption of the Second World War made compassionate tales about any of America's enemies, be they nations or criminals, taboo. Henri Young's struggle with the Rock and with himself would continue, in an invisible world.

![]()

![]()